Huang Jieli, who ran a Chinese ride-sharing business called Hitch, was invited to a wedding in March. One of her drivers was getting married to a woman who had once been his passenger. Thanks, the invitation said, for getting them hitched.

Didi Chuxing, Hitch’s corporate parent and one of the world’s most successful and valuable start-ups, once cheered these stories of young love. Like so many other Chinese internet companies, Didi explored all kinds of ways to bring in new users, including social networking.

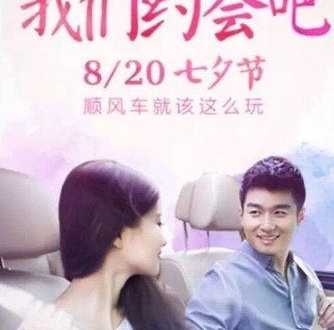

So through suggestive ads hinting at hookups through driving, Didi pushed Hitch’s romantic possibilities. In a 2015 interview with the Chinese online portal NetEase, Ms. Huang compared Hitch cars to cafes and bars.

“It’s a very futuristic and very sexy scenario,” she told NetEase.

Today, that attitude looks careless and incompetent. Two female Hitch passengers in the past three months have been raped and killed by their Hitch drivers, according to the police. Now Ms. Huang is out of a job, Didi is pledging to overhaul its business, Chinese consumers are calling for a boycott and the internet industry is getting a much-needed reminder of the consequences of its actions.

It’s a rare moment of self-reflection in China’s internet industry, which has grown to rival Silicon Valley in both size and influence. Two Chinese companies, Tencent and Alibaba, rank among the top 10 publicly listed companies in the world in valuation. Four of the 10 most valuable start-ups are from China, according to CBInsights. One of them is Didi, which ranks second only to Uber.

The problems aren’t unique to China. Uber has grappled with its own safety issues, while Facebook has belatedly come to terms with how its reach can be misused and abused.

But the potential for abuse in China is severe. Corporations are subject to little scrutiny from state-controlled media until problems spin out of control. Spotty enforcement and slow lawmaking leave the public less protected from exploitation. Chinese people are fixated on their phones, spending four more hours on average a week online than Americans. The industry’s extreme growth — the number of internet users has doubled, to 800 million, in eight short years — has created a culture in which companies prize money over users’ well-being.

Didi itself admitted this week that it had lost its way. In a statement on Tuesday, it said it would stop using scale and growth to measure its success.

“In the past few years we forged ahead wildly, riding on aggressive business strategies and the power of capital,” the company said in the statement from Cheng Wei, its chief executive, and Jean Liu, its president. In the face of lost lives, the statement said, “the whole company started to question whether we have the right value system.”

The Chinese public has asked similar questions. In the aftermath of the two assaults, Chinese media has uncovered dozens of others over the years. It also found past advertisements for Hitch that featured lewd double entendres and other language that could suggest a female passenger might welcome an advance from her male driver.

“Truly disgusting, despicable marketing for Didi Hitch that’s all sexual innuendo and all about ‘picking up’ girls,” said Rui Ma, a technology investor who works in both Silicon Valley and China, on Twitter. She added, “Didi are you running a service for sexual predators or a ride hailing app?!”

While it wasn’t obvious to female passengers that their drivers might want to hook up, the drivers knew. Until Didi deactivated Hitch, the car-pooling service allowed drivers to share comments with other drivers on the looks of their passengers, leading some male drivers to seek out the ones others had declared attractive.

The problem goes well beyond Didi. China has grown so fast that many facets of life — shopping, online banking, transportation — lack the sort of established incumbents common in the West. Tech companies can swoop in and become dominant in those areas. That makes Chinese companies appealing to investors. It also makes them potentially dangerous.

My conversations with Chinese tech companies and their investors, including some from the United States, revolve around user growth and the amount of time they can keep users glued to apps. On occasion I asked why they lent their technology to the government for surveillance, or what they thought the social impact might be from the videos, games and endless feeds of mind-numbing information they send to the public. They either gave me blank stares or said their technologies were merely neutral tools.

Some in China are comparing Didi’s problems to Baidu’s. Sometimes known as the Google of China, Baidu dominates the search business in the country. Two years ago the company was harshly criticized for foisting ads for fake medical treatments on the public. Baidu apologized after each incident came to light, but some Chinese users are still angry at the company.

“No matter how we complain or criticize, bad companies, be it Didi or Baidu, simply won’t change,” Ye Ying, editor of The Art Newspaper China, wrote on her WeChat timeline. “I’ve stopped using Baidu long time ago. Should I delete the Didi app as well?”

The scandal also exposes a wider industry problem with sexism. Tencent apologized last year after a video emerged of a corporate event that featured female employees trying to open water bottles tucked between men’s legs. Two years ago, Alibaba’s finance affiliate, Ant Financial, pulled a new social feature on its app that led to women posting suggestive photos of themselves to attract rich men. Some tech companies have posted job ads only for men. One of them was Didi.

Even with women in top jobs, the industry can’t seem to shake the attitude. Ms. Liu is probably China’s most prominent female technology executive.

Hitch’s suggestive strategy was overseen by Ms. Huang. In one corporate video the company compared her to Hua Mulan, the female warrior of ancient China, and promoted her as a skilled executor of the company’s vision. The video’s English title is “Lean In, Jelly,” using her English name.

The question now is whether Didi, and executives in the rest of the industry, can root out those attitudes to protect users.

“Without the interference of a value system, the vast majority of them will choose their job performances over users’ safety,” wrote Feng Dahui, a former Alibaba executive and industry critic, in a WeChat post. “This is the ethical dilemma of most internet elites.”

Follow Li Yuan on Twitter:

@LiYuan6.

Interested in All Things Tech? Get the Bits newsletter delivered to your inbox weekly for the latest from Silicon Valley and the technology industry.